Friday, 18 December 2009

Snapshots of My Landlady

Most likely because of her traumatic memories, my landlady is also obsessive about security. During my first months here, she advised that I should come home before 8 o’clock in the evening, the time which she habitually locks the front gate. My bicycle must be parked inside the ground floor apartment (I live on the second floor). Lock the bicycle around the wheels if I return home late; otherwise, she warned, thieves would come.

Taking her advice, whenever I returned home late from a drink or dinner, I would lock according to her instructions. Later on, however, I noticed that she would always wake up in the middle of the night and take my bicycle back into the house. She just did not feel safe. Also, the next day, I would have to sit through her ranting, in Khmer, most likely about the dangers in the streets.

After a few months, she asked that I lock my bicycle to the metal staircase if I were to return late.

With her son working in Battambang Province, she lives with her two busy grandchildren. Both of them are universities students and work part-time. Therefore, she spends many mundane days alone, watching TV, washing clothes, cooking food, doing housework and running errands. She is usually the only one to greet me when I return home from work.

Because of her alertness and her (sometimes-over-the-top) sensitivity to safety and security issues, it was uncommon that she did not sense my coming into the house. That evening, she was so absorbed in the television that she only turned around in surprise when I sat down in a chair next to her.

She was watching a volleyball game. When she saw my puzzled face, she briefly withdrew her attention from the television screen. In an instant, as if gaining a rare wave of energy, she waved her arms, stamped her feet and began speaking in Khmer in a rather loud voice. I continued to look at her, puzzled. But the more puzzled I looked, the more frantically she pointed to her arms and knees and tried to make me understand.

From my limited Khmer, I understood that the game was volleyball – g’baal p’dtea and that the competition was held at the Olympic Stadium in Phnom Penh. From the broadcast, it also looked like that the Cambodian Team had won two sets already and was ten points ahead of the Indian Team in the third set. Whenever the Cambodian Team score, I could see my landlady slowly lifting the edge of her lips and gradually forming a reserved smile. The motion was subtle; but for her, this action culminated from much excitement and joy.

Watching the game, I could only see poorly trained players who could barely control the ball. Rarely could I see the effortless jumps, accurate passes, impenetrable defence and powerful spikes demonstrated by world-class volleyball players at the real Olympic Games held at furnished and well-maintained stadiums. My landlady must be happy just because she supported the home team.

With both teams weak in their volleyball techniques, each play was short and the scores moved along quickly. Very soon, the score became 20-10 – the Cambodian Team only needed five more points to win. A Cambodian player served again and the Indian players could not return the serve and the ball bounced off to the spectator stand. I was about to smirk at this ridiculously incompetent play, tell my landlady that I have had enough and go upstairs to prepare dinner.

But then, for a split second, I noticed something strange about this Indian player: he had no arm!

At a closer look, among the other players, quite a few had artificial limbs. Most probably, the rest of the players had other less visible forms of disabilities, such as mild epilepsy, deafness and learning disabilities.

Almost immediately I felt ashamed of my silent criticism and negative thoughts. Coming from a war-striken era, my landlady must have seen many people disabled by landmines, machetes, guns and accidents. She would understand the unspeakable emotional and physical experienced by those stripped of good and healthy bodies. Among her close relatives and neighbours, there may be individuals who were discriminated for their disabilities and were demoted to living in shame as outcasts. There must be families with breadwinners handicapped by landmines and fighting and could no longer find productive work. There would be many children who were denied education and social support due to injuries from a young age. Encountering disabled people and dealing with the hardships stemming from disabilities were inevitable parts of Cambodian life.

The victory of the Cambodian Team in disability sports therefore represents more than winning the Trophy. This victory indicates recognition for physically and intellectually handicapped people and honours their efforts to overcome physical limitations and accomplish “the impossible.” In Cambodia, this message serves as a crucial encouragement for many disadvantaged groups – not only the disabled. Many more who live in chronic poverty, suffer from diseases (e.g. HIV/AIDS) and are forced into demeaning jobs (e.g. prostitution) may be encouraged to take a bold step for their own well-being. The society may have doomed them, but they can – if they want – to live a life of dignity and be inspiration for others.

During these few months in Cambodia, I have heard about and met people who live with disabilities and diseases as well as those suffering from chronic poverty. The media also often reports about women forced into demeaning occupations and children working in the worst forms of child labour. However, there are also many international organizations, NGOs and civil society groups which work actively to withdraw people from destitute. Their success stories should be publicized to direct disadvantaged people away from fatalistic and pessimistic attitude; beneficiaries should stand out as role models and spread the message that individuals can make a different in their own lives.

At the end of broadcast, my landlady expressed joyously, “S’bay jet na.. m’sell min grom Kampuchea ban ch’nea dae… s’rok ey? Knom pleck hi… Bundai, s’bay jet na… (I am very happy… Yesterday, the Cambodian Team won also… Against which country? I forgot already… But anyway, I am very happy…)” She went on and on as I gestured goodbye and moved slowly out of her living room.

Friday, 11 December 2009

The Difficult Peace

A few days after reading this news article, on 27 November, a Filipino friend invited me to watch a Filipino staged play, the closing performance of the Mekong Arts Festival in Phnom Penh. Coincidently, the play’s plot depicts conflicts in southern Philippines.

In the story, Ismael and Isabel were childhood friends in a religiously diverse community. Ismael’s parents, Muslims, were killed by intolerant Christian radicals. Isabel, though a Christian, was also separated from her parents during the armed conflicts. The fighting destroyed their village and they made their way to Manila, the capital city. There, Ismael joined a Muslim gang and terrorized Christians through kidnapping and assassination. Isabel became a maid for a Christian British family.

The story then fast-forwarded to two years later. The two main characters crossed paths again as Ismael attempted to kidnap Isabel’s master. Reminiscent of their friendship prior to the conflicts, Ismael and Isabel reconciled. Hand in hand, they fled to a new world without any conflicts.

Amidst lively dances and upbeat music, the play advocated for peace. The playwright certainly conveyed the urgent need to mitigate hatred and create a harmonious society.

When I first arrived at Phnom Penh, I followed the United Nations protocol and reported to the UN Department of Safety and Security (UNDSS). The officer there assured us “newbies” that Cambodia is “very safe.” But as I stayed on longer, I learned that beneath this peaceful façade, there are actually hidden fissures:

- Territorial disputes between Cambodia and Thailand over the Preah Vihear Temple, a UNESCO World Heritage Site in northwestern Cambodia. The Site now sits within the Cambodian border but the Thai authorities also claim sovereignty. In an attempt to uphold national pride, the Cambodian Prime Minister recently received Thaksin, the fugitive former Thai President, and appointed him an Economic Advisor. This action may heighten diplomatic tensions (ambassadors have already been recalled) and spark new fighting at the border.

- Sam Rainsy, Leader of the Cambodian opposition party, removed six markers along the Cambodian-Vietnamese border in Svay Rieng province in October 2009. Rainsy undertook this provocative action in reaction to complaints that Cambodian farmland was illegally occupied by the Vietnamese. Indeed, the two countries has 1,270km of contentious border. Some efforts have been started since 2006 to demarcate the border but disputes still arise occasionally.

- Entertaining private sector or individual interests, government officials from some provinces and districts have evicted many families and ignored the hardships experienced by the evictees. In addition, the recent relocation of some 40 HIV affected families to the outskirts of Phnom Penh have prompted international outcry. Rights groups especially cited the oppressive heat, lack of access to health care, poor supply of food and limited job opportunities at the relocation site. Some activists even called the area an “AIDS colony.” Prolonged dissatisfaction over these forced evictions may gradually fuel public action and unrest.

- Corruption within the government bureaucracy has potential to stir up public dissent. According to Transparency International, Cambodia ranks among the most corrupt nations in the world, just on par with such countries as Laos, Tajiskistan and the Central African Republic. Without strong political commitment and government institutions to formulate and implement anti-corruption laws, many Cambodians and foreign businesses have to pay bribes. Corruption may also limit the public funds available for concrete reforms and public welfare. If public discontent against corruption and ineffective public services reaches a critical mass, there may more and more protests against the government.

Further reading

Mekong Arts Festival 2009: Weaving Cultures, Weaving Vision

“Cambodia Tit-for-Tat over Thaksin,” BBC, 6 November 2009

“Sam Rainsy Uproots Vietnamese Border Markers,” Phnom Penh Post, 27 October 2009

“AIDS Day Event Sparks Debate,” Phnom Penh Post, 2 December 2009

Tuesday, 8 December 2009

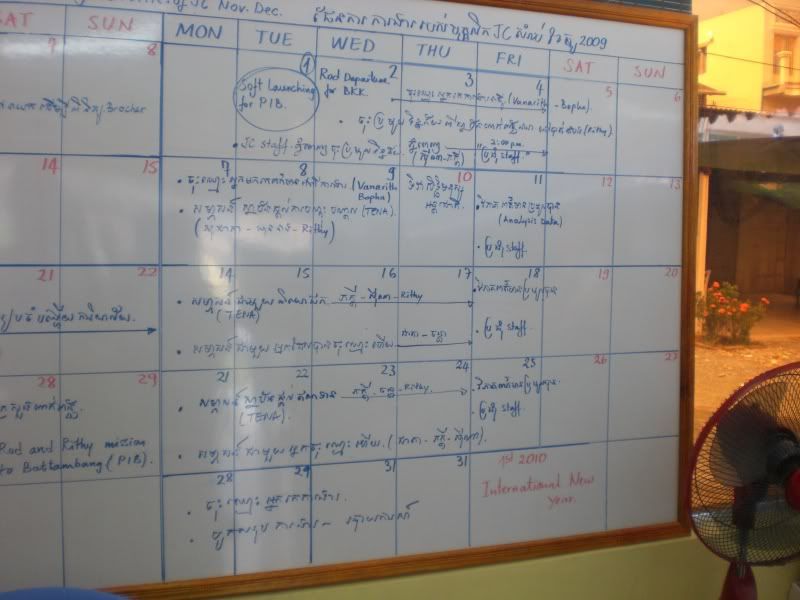

Job Centre Launch Photos

Our panel of distinguished guests, including HE Mr. Laov Him (most left), Director General of the Department of Technical and Vocational Education and Training (DTVET); HE Mr. Pich Sophoan (centre), Secretary of State, Ministry of Labour and Vocational Training; Ms. Carmela Torres, Senior Skills Specialist, ILO Subregional Office; and Mr. Tun Sophorn, National Coordinator, ILO Cambodia.

Front entrance of the Job Centre, together with the logo of the National Employment Agency (NEA) which was established by a government sub-decree this year.

Friday, 4 December 2009

I Need Employment Advice?!

On the contrary, in Cambodia, I have seen the problems of a “youthful” nation. Although the economy grew at above 10 percent between 2004 and 2007, the increase of job opportunities remained sluggish. In effect, almost 300,000 youth flood into the market each year. But less than 40 percent of them can find employment.

Coming on the heels of the global economic crisis, these unemployed young people are experiencing more severe hardships.

These labour market conditions contributed to an initiative from the Royal Government to strengthen employment services through the establishment of Job Centres. Ideally, these public employment services will serve as the basic steps to full employment of individuals at various skills levels. However, the extent and the variety of services these Centres can offer likely depend on the different countries’ market environment and the availability of financial resources, political commitment and capable personnel.

According to the International Labour Organization (ILO), an efficient and functioning labour market should comprise a wide array of employment services:

- Employment counselling: information on job search techniques, advice on small and medium enterprise (SME) development and linkage to job fairs/clubs, etc.

- Vocational counselling: information on skills requirements and training institutions, referral to universities, apprenticeships and on-the-job training, linkage to entrepreneurship and financial literacy training, etc.

- Career counselling: information on current and projected jobs in demand, assessment of interests, aptitude and abilities, information on occupation and work conditions, introduction to employment networks, linkage to volunteer work, summer job, part-time work, internships, etc.

- Labour market adjustment programmes: registration of individuals for unemployment insurance, collection of unemployment insurance claims, advice from trained social worker and counsellor on other personal issues

- Labour market exchange: participation from employers for regularly updated job postings

In Cambodia, although the demand for these services has especially intensified, experiences from the Job Centres highlight the limitations to deliver job placement services, manage labour market information and analyze data and trends. For instance, some employers would have few incentives to use employment services for finding suitable job candidates. They also have little immediate motivation to contribute to setting up a labour market information system. As an example, the garment industry employs mostly young women with little education and few vocational skills. Thousands of low-skilled women in Phnom Penh and other provinces would desire factory work for stable incomes. Since factories can readily replenish worker losses, investing extra time and resources in employment services may become an unnecessary nuisance.

However, Job Centres would not succeed unless employers also participate and provide precious information on job openings and future skills needs. This dilemma hence suggests the need for an assertive and confident team of Job Centre staff. These staff members should proactively liaise with employers and make every attempt to solicit needed information from the private sector.

Noting the vast supply of low-skilled and undereducated workers, Job Centres would likely be overwhelmed by job-seekers who have few employable skills. In effect, one must bear in mind that even the best employment services may not help all unemployed people to seek jobs immediately.

What, then, can the Job Centres offer clients who are not matched to any job or training opportunities? In the Cambodian context, Job Centre staff members would likely be the unemployed people’s only source of information about the labour market. At the least, these trained counsellors and analysts should offer timely advice on jobs and skills in high demand and encourage the jobless to consider an alternative career path. In cases where the jobseeker is committed to certain types of employment, the Job Centre should provide information on the skills needed for the desired job and the availability of relevant training opportunities. More crucially, counsellors should encourage their clients to be realistic about their wishes and their actual skills levels. In the end, every client should leave the Job Centre with better knowledge about the job market, their own skills and next steps to be taken.

Surely, there would also be a group of jobseekers who are relatively qualified and more motivated. The Job Centres should have a clear line of services to help those who are more likely to succeed. For instance, would the Job Centre help to arrange for interviews with potential employers? Would these candidates be referred to entrepreneurship or other vocational skills training? And at what point should clients be advised on microfinance opportunities? In short, the Job Centre team should ponder on these questions and take concrete steps to create solid linkages between workers, employers and training providers.

In addition to concerns about market data collection and service delivery, knowledge management would also likely be a challenge. To match the information of thousands of unemployed people with the specific skills demanded by hundreds of employers, the Job Centres require an efficient data processing system. As some examples, electronic forms, data analysis software and other programmes for inputting, collating and comparing information would be most helpful. In the longer run, as more and more Job Centres become operational within the country, networked computers may be needed for exchanging labour market information at various localities.

Most recently, on 24 November 2009, the Ministry of Labour and Vocational Training and the ILO launched the first Job Centre in Phnom Penh. On 1 December, the second pilot Job Centre was opened in Battambang Province. The challenges elaborated in the previous paragraphs will likely become more and more real. Will the unemployed flood the Job Centres? Or will there be no clients? Will the employers buy into employment services? Will training providers be willing to take advice from the Job Centres? How many jobless persons will be directly linked to jobs or training courses? And how many more will be indirectly benefited, such as through obtaining a better understanding of labour market conditions? These questions may be answered in the next few months.

References:

“Employment Services: International Perspectives and ILO Experience,” PowerPoint Presentation for the Employment Services Workshop in Vientiane, Lao PDR, 13 November 2009

“First of 11 Job Centres Opened in Capital City,” Phnom Penh Post, 25 November 2009, http://www.phnompenhpost.com/index.php/2009112529759/Business/first-of-11-job-centres-opened-in-capital-city.html